"It's just the right city for the tournament": How Gothenburg became a hockey city and host for the 2024 World Juniors

Gothenburg is now one of Sweden's foremost hockey cities, but what most people don't realize is the recency of that phenomenon and how unlikely it was in the first place.

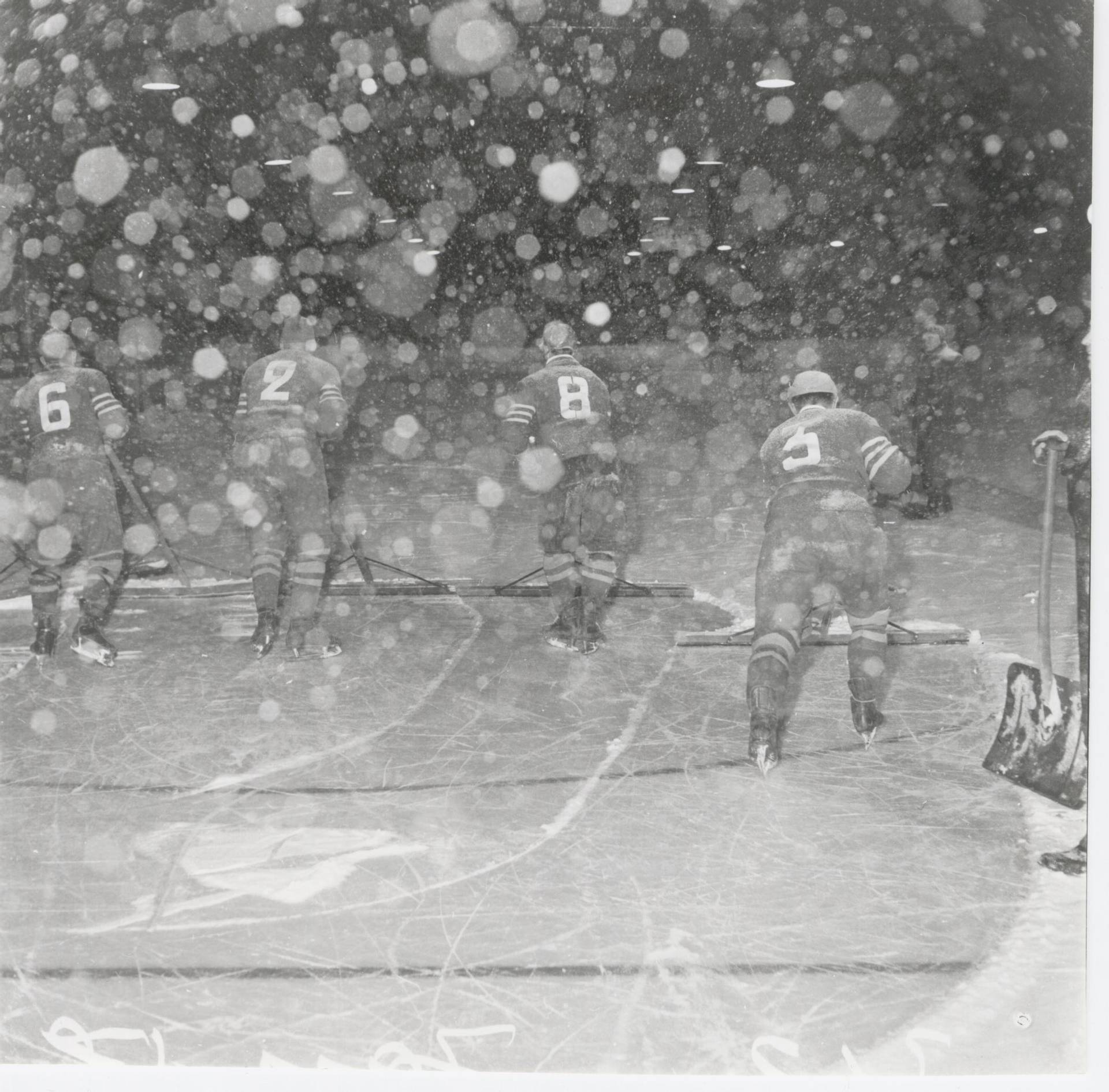

Situated on Sweden's west coast where warm winds from the North Sea make for volatile but mild winters, Gothenburg's climate isn't particularly well-suited to the sport – some have taken to calling it Little London because of its rainy, dark aesthetic. In a Nordic country where most could rely on the weather to give them a solid five months of hockey weather, this city couldn't reliably bank on much more than half of that cumulatively.

It seems like a trivial matter now that indoor arenas are the norm in every corner of the hockey world, but it was an existential one for the sport in its first few decades of popularity in Sweden. It wasn't until 1955 that the country erected its first indoor ice hockey stadium, the Hovet Arena (known at the time as Johanneshovs Isstadion) in Stockholm.

Gothenburg, meanwhile, had to wait until 1967 to get its first indoor arena, the Frölundaborg stadium that's going to share hosting duties at this year's World Junior Hockey Championships.

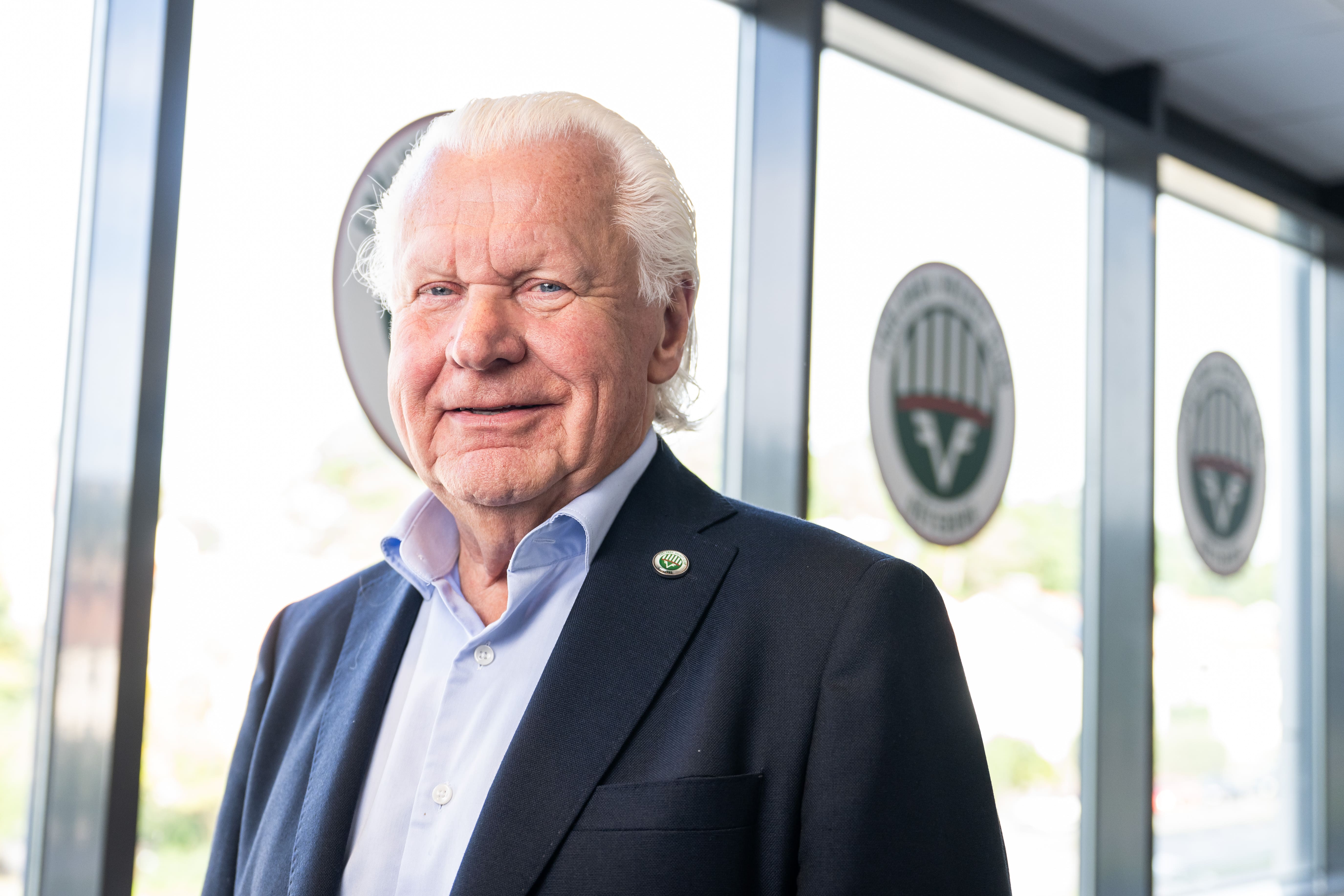

Szymon Szemberg, who has been involved with Swedish and European hockey for decades, serving as a Chief Operating Officer and one of the minds behind the founding of the Champions Hockey League as well as serving as a Dir. of Communications with the IIHF from 2001-13, says that this moment was critical to the development of hockey in the region.

"Gothenburg was very late to hockey. Gothenburg was a very, very underdeveloped hockey town until the mid-fifties when the first artificial ice rink was built, and it wasn't covered. The first covered rink in Gothenburg is the rink which will be the secondary rink for this World Juniors tournament, called Frölundaborg, built in 1967. It took until 1967 before Gothenburg got its first covered rink."

Were it not for the unlikely ascent of Frölunda to the top division, they might not have even got the Frölundaborg when they did. Plans were in place to build the Scandinavium, Frölunda's rink and the primary one for the World Juniors, for some time, but it had almost taken on meme status during three decades of constant stops and starts. This truly was a necessary pivot because of the unlikely, sudden success of Gothenburg's team.

"Well, the Frölundaborg was built extremely quickly because Frölunda became a major league team in the early sixties. This is when they started to climb through the divisions and reached the top of Swedish divisional play," Szemberg said. "You know, in the European system, you start in Div. 5 and work yourself up to Div. 4, 3, 2, 1 until you reach the top. The system with expansion teams doesn't exist in Europe.

"So they became a big team in Sweden in the early sixties, and they played in the big outdoor soccer arena. Eventually, they realized that this cannot be; that such a good team plays in an outdoor soccer arena when often it was raining in Gothenburg. So we had to build an arena and this arena was built very quickly. And this arena was actually, to a large degree, funded by the citizens of Gothenburg essentially that created a scheme that you could open a bank account in a certain bank and you put a certain number of your savings into the hockey arena. So, the hockey arena was actually built by the citizens of Gothenburg thanks to this phenomenal idea that was launched by Ulf Sterner's brother, Ove Sterner."

That worked in a pinch, but Gothenburg would eventually need to get the Scandinavium back up and running. Frölunda was only gaining prestige, the locals finding themselves more attached to this upstart sport. It had to happen.

The ins and outs of how that came together warrant an article all its own, but here's what you need to know: Eventually, a Swedish government made building the Scandinavium a part of its platform, won its election, and found the funding necessary to get it across the finish line.

"It was a lot of ups and downs, but they eventually started construction on the Scandinavium in 1969, and it was opened up in May of 1971. It can hold 12,000 spectators, and it became Frölunda's stadium."

For almost two weeks starting on Boxing Day, Scandinavium and Frölundaborg will be Sweden's home stadium as they try to capture World Juniors gold on home soil for the first time.

This is the story of how Gothenburg became a hockey city, their home team a model franchise, and the biggest tournament in junior hockey came to this unlikely yet fitting destination.

"The first three players from Sweden to go to North America… all of them came through Gothenburg."

Gothenburg has become the place to go if you want to reach the NHL, but curiously, that dynamic hasn't extended to those born in the city's limits.

There are 143 players who skated in at least one NHL game that came up through Frölunda, but only 22 were born in Gothenburg. You might expect an asymmetry between those two figures, but that's something else entirely. The ratio is closer to three-to-one if you look at Stockholm and its two teams, Djurgårdens and AIK.

It's always been that way, too. For as long as Gothenburg's been producing NHL talent, it's done so by identifying talent in the outlying areas and developing it through Frölunda's system.

"This is actually a very interesting thing," Szemberg said. "The first three players from Sweden to go to North America – all of them eventually came to the NHL – all of them came through Gothenburg, or rather, they went through Gothenburg, but they all came from a part of Sweden called Varmland, which is approximately 250 kilometres north of Gothenburg."

Ulf Sterner is probably the most famous of the three – not just in Gothenburg but in Sweden. He became the first Swede to ever skate in an NHL game, playing in four contests for the New York Rangers before eventually having to come back to Sweden.

"Ulf Sterner became the first European player to play in the NHL, also for the New York Rangers, but he lasted only four games. And Ulf Stener was part of this 1962 Colorado Springs team. So there you have the second player."

Juha Widing became the first Swede ever to play Canadian junior hockey, joining the WHL's Brandon Wheat Kings before eventually making his way to the New York Rangers and carving out an eight-year NHL career.

"He was actually born in Finland, but that's more of a trivia thing. He came to Sweden as a small child and he started to play hockey in Varmland for a small club called Grums IK and he actually was one of the few players who played for Frölunda, which in those days in the fifties and early sixties, there was a soccer club in Gothenburg called GAIS and they for a few years had a separate hockey program. So for a few years, Widing was the first player to play in North America, but he went through junior."

Then there's Thommie Bergman. He played parts of six seasons in the NHL and is still in the league as a scout with the Toronto Maple Leafs.

"[Bergman] was actually one year ahead of Borje Salming in the NHL," Szemberg said. "It is correct that Borje Salming was the player who opened the floodgates for Europeans, the trailblazer in the 73-74 season, but Thommie Bergman was one season ahead of him…So Thommie Bergman, for the Detroit Red Wings in the 1972-73 season, he was the first European to play a regular shift for an NHL team as a defenceman."

The first player from Gothenburg to come up through Frölunda was Jörgen Pettersson. His Elite Prospects page starts right around when he was 18, with Frölunda, and he's the city's champion.

"Pettersson was the first Gothenburg and Frölunda-developed player when he signed with the St. Louis Blues in 1980-81. So those players I mentioned to you, they were 10-15 years earlier, but Jorgen Pettersson was the first player who was from Gothenburg, developed in Gothenburg, developed in Frölunda, who signed with an NHL team. He's credited as the first Gothenburg-born and bred player who showed the way for other Gothenburg hockey players born there."

Like almost everyone else in Swedish hockey who makes it to the show, Pettersson eventually returned to Sweden at the end of his career, but there wasn't much gas left in the tank. On and off the ice, it seems. He didn't take an interest in joining Frölunda's front office. He's not involved in youth hockey in any capacity. And that's by design. You want to talk to him? Your best bet is running into him at a Frölunda home game, where he's still seen from time to time as a spectator.

Still, his place in Gothenburg hockey history is enormous. Young players still mention him as someone they look up to. His No. 19 jersey hangs from the rafters of the Scandinavium, home to the team that got it all started for Pettersson, Frölunda.

Their beginnings were incredibly humble.

The story of Frölunda is fascinating. The organization was founded in 1938 but didn't play hockey until after World War II, in an outdoor arena in the Göteborgsserien (the Gothenburg Series), mostly with former bandy players. Bandy, if you're not familiar, is a lot like hockey, but it's played with a ball on a larger frozen field and comically large nets.

"Their beginnings were incredibly humble. In the beginning, most Swedish players who took up hockey in the twenties were bandy players," Szemberg said. "It was exactly the same thing in Frölunda. The first team that Frölunda played with in 1946, basically everyone was a bandy player with their bandy club.

"So you know in Europe, we have the system with sport clubs. So one sports club can have hockey, basketball, handball, soccer, athletics – whatever. So this has more and more disappeared because of economics, but this was the case for many, many years. Frölunda was a club that played bandy, handball, soccer, and other sports. It started in 1946 after World War 2, but it took them until 1961 before they became an established club or team in the top league.”

From there, Frölunda took off. It got the Frölundaborg built in 1967, six years after they joined the highest level of Swedish men's hockey. Four years later, they would have the Scandinavium to play in. And the environment was always electric.

“What changed things was that it became popular very quickly. So when they played in this outdoor soccer arena before the Frölundaborg was built in 1967, they immediately drew big crowds. So often, they had crowds of over 20,000 people, which is a lot. What made Frölunda what it is today is this period between 1961 and 1967 when they became so popular despite not having a real hockey arena to play in. They were the team that played in this outdoor rink in a huge soccer stadium, which was totally oversized for hockey, but during those years, they built this relationship with the Gothenburg public and audience that took on this new sport of hockey.”

In many ways, Frölunda has been a victim of its own success since. Many of the best players who make their way to Gothenburg are there for a good time, not necessarily a long time. They have NHL aspirations and know this is the place to go if they want to realize them.

The result is that Frölunda has been about as consistently good as any professional sports team can be in the regular season, but they haven't won many titles, just two to date. The same is true in the SHL playoffs, where they've only won three SHL championships, two of them fairly recently. They also haven't played a single game in the HockeyAllsvenskan since the 1994-95 season though.

“One thing I have to mention is that Frölunda is the one club outside of North America which has had the most players drafted to the NHL, which is 105,” Szemberg said. "This is everyone who were from the Frölunda program or went through the program when they were drafted. No other program in Europe has had as many players drafted as Frölunda has.'

“Frölunda had this aura that if someone goes there, 1) I have the best chance to develop into a solid player, 2) I have the best chances to be drafted or signed by an NHL club. An example is Erik Karlsson. He comes from a different part of Sweden, but he came to Frölunda, was developed there, was drafted, signed and became a superstar. He went to Frölunda because they have a good program and a good history of developing players that get to the NHL.”

“It was about giving the kids a lot more confidence, playing them earlier on the big team.”

When Gothenburg decided to make a push to secure the tournament back in the mid-10s, it was Mikael Ström who seemed like the obvious choice to spearhead the operation. With a résumé like his, it's not hard to understand why either.

“I started my career with the Swedish Ice Hockey Association as a hockey consultant for the federation and the area around Gothenburg,” Ström told EP Rinkside. "I’m based in Gothenburg. I started in 2003. Before that, I coached junior programs in Gothenburg, my last coaching job was the TV-Pucken for Gothenburg and I do that this year as well. But I was away from Frölunda for three years, between 2003 and 2006, and worked in that consultation to educate youth and junior clubs around Gothenburg.

“Then Frölunda called me again, and they said, ‘Maybe it’s time for you to come back to the club and work with the program full-time,’ and I’ve been there since 2006 now. In the first two years, I was only with the youth program. Then in 2009, I took the general manager job of the junior program in Frölunda. Since then, I thought that maybe I will do something else, so I took a break from that. I’ve been in the Frölunda junior program since 2009 and the sort age group that I’ve worked with is under-16 to under-20. I’ve got two children, two boys around 15-years-old and 20-years-old. The youngest plays hockey himself, so I try to follow his career, and I’m also one of the coaches for his youth program.”

The TV-Pucken is a historic tournament in Sweden for under-15 men's hockey players, with districts from all over the country participating. It's a stepping stone for many as they work toward a professional hockey career, almost a right of passage for those in Sweden.

It was named TV-Pucken because, you guessed it, the games were all televised back at a time when that wasn't even a given with most league games – this tournament dates back to the 1950s too, so that really means something, but it's actually diminished in that respect with time, to the point that only playoff games are broadcast now.

Now the World Juniors are almost taking its place in Swedish hockey culture in a way; not the exact same, but close enough. This isn't a country with much of a junior hockey culture, but that's starting to slowly change.

For Ström, making that happen has been a project that he's taken head-on at the grassroots level with Frölunda as a general manager with the youth program. It wasn't enough to be a stepping stone for the rest of Sweden on the path to their NHL dreams; this city and this area had to develop its own talent, too.

“It’s a really good area for hockey in Sweden. Of course, it’s not a traditional hockey area from the beginning though,” Ström said. "I think that in the last 50 years, we’ve worked together with the youth clubs in the area, the under-17 youth club that’s about 30 kilometres away from Gothenburg, so to build it into a hockey area, always with the youth clubs.

“We helped them, and we worked together with them, and I think we’re a really good place to be a hockey player now. It’s something for us to be the biggest club in the area for others to see, and we try to help the smaller clubs in the best way. Of course, in the end, when the players are 14- or 15-years-old, the best players move on to our academy and start their careers when they are 15 and up. So, if you’re a junior in our area, you see Frölunda as the top, and we have a good record, both in points and for having young players in our SHL team. We’ve developed our program to help our players be the best in the world. There are a lot of players in the NHL who went through Frölunda. We’re really happy about that of course.”

Two things happened in 2012 that sent Ström's project into overdrive. First, Mats Grauers came on as chairman, leaving a wildly successful handball club just outside of Gothenburg called IK Sävehof.

Then, after three separate tries, they courted Detroit Red Wings Dir. of European scouting Håkan Andersson to their board for a partnership that lasted three-plus seasons. This sent Ström's project into overdrive.

Andersson told him that in a 4.5-hour conversation, he would join, but only if they would listen to his suggestions. That started with a few critical hires.

“I gave him the list of people I wanted to hire, which included Roger Rönnberg and Robert Ohlsson, because I knew who they were from the World Junior team. Once they came in, we had the same ideas. It was about giving the kids a lot more confidence, playing them earlier on the big team, but before you play them on the big team, train them harder on the junior team – higher demands, better training, better information.”

The focus on player development paid immediate dividends. Frölunda won an additional nine games in Rönnberg's first season behind the bench, and they went one round further in the SHL playoffs each additional season until they captured a title in 2016. The average age of Frölunda's SHL roster in the year that preceded his arrival was 26.71, but that had fallen to 25.33 by the time they won their championship.

Of the 18 players to be born in Gothenburg and make it to the NHL through Frölunda, five have played under Rönnberg; put another way, his tenure has spanned 16 percent of the club's time in Sweden's highest level of professional men's hockey and produced 27 percent of its born-and-bred NHL talent.

“We would get together every day and talk about development, the Swedish federation, junior hockey – there was a bunch of us that kept saying, I don’t know why they don’t place better demands on the players, train them harder," Andersson said. “We were all saying that these young kids can play in the SHL much earlier than they are. If somebody just gave them the proper training and the proper chance, we think they can play. This is how I would like to see it done. When you have an injury in your lineup, you don’t search the market for a 30-year-old; you find someone in your program who is a junior. Give him a shot on the big team.”

“Gothenburg is ready for the tournament”

The timing of Frölunda's youth movement couldn't possibly be any better. This time 20 years ago, nobody really cared about the World Juniors in Sweden. It wasn't even nationally televised. The running joke was that their junior leagues were for parents and partners. That's slowly changing now, and it's not hard to imagine a scenario where there's an audience for this product all year round.

“Sweden does not have the same World Juniors culture as Canada,” Szemberg said. “It is growing, and there is more interest, and it is becoming a part of our holidays, but this is a new phenomenon. For most Swedish hockey fans, the thinking has always been, ‘Why would I watch them as juniors when I can just see them in the SHL or in the NHL if they are any good?’”

The logic, however cruel or unfamiliar to a North American audience, is reasonable enough. Most teams in the J20 Nationell, which is the Swedish equivalent of the CHL, have a parent club in the HockeyAllsvenskan or the SHL – sometimes both! If you're based in Gothenburg, you can just go to a Frölunda game; if you're based in Sault Ste. Marie then the Greyhounds are the only show in town, and the nearest NHL team is the Red Wings, one border crossing and about a five-hour drive away.

That's starting to change. The catalyst was the 2007 tournament in Leksand, the first that was nationally televised in Sweden. Suddenly, people in the Scandinavian nation could see what we'd known across the Atlantic for almost a decade at that point: That this is as good as hockey gets. Then when they won their second gold in tournament history in 2012, it really took off.

Sweden's head coach at this year's tournament, Magnus Hävelid, has seen that development firsthand. He was with the federation from 2000 to 2004 in his first stint, and then he joined them again in 2015. He's coached at the tournament twice already, first as an assistant in 2016 and most recently as the head coach last year in Halifax.

“I think it’s starting to get quite big actually. I think it’s become a tradition in Sweden for at least 10 years. When they won it in Canada back in 2012, since then it’s become very popular,” Hävelid said. “Everyone sees it on the TV. For us, I think it can help new players come in who might want to learn. As I told my players now, we want to give the players in the clubs at home who are 10- and 12-years-old inspiration. So that will probably increase the numbers of hockey players – that’s good. They’ll be here as spectators on the TV or in the Scandinavium and see the games, so that’s a great opportunity for us as a hockey nation.

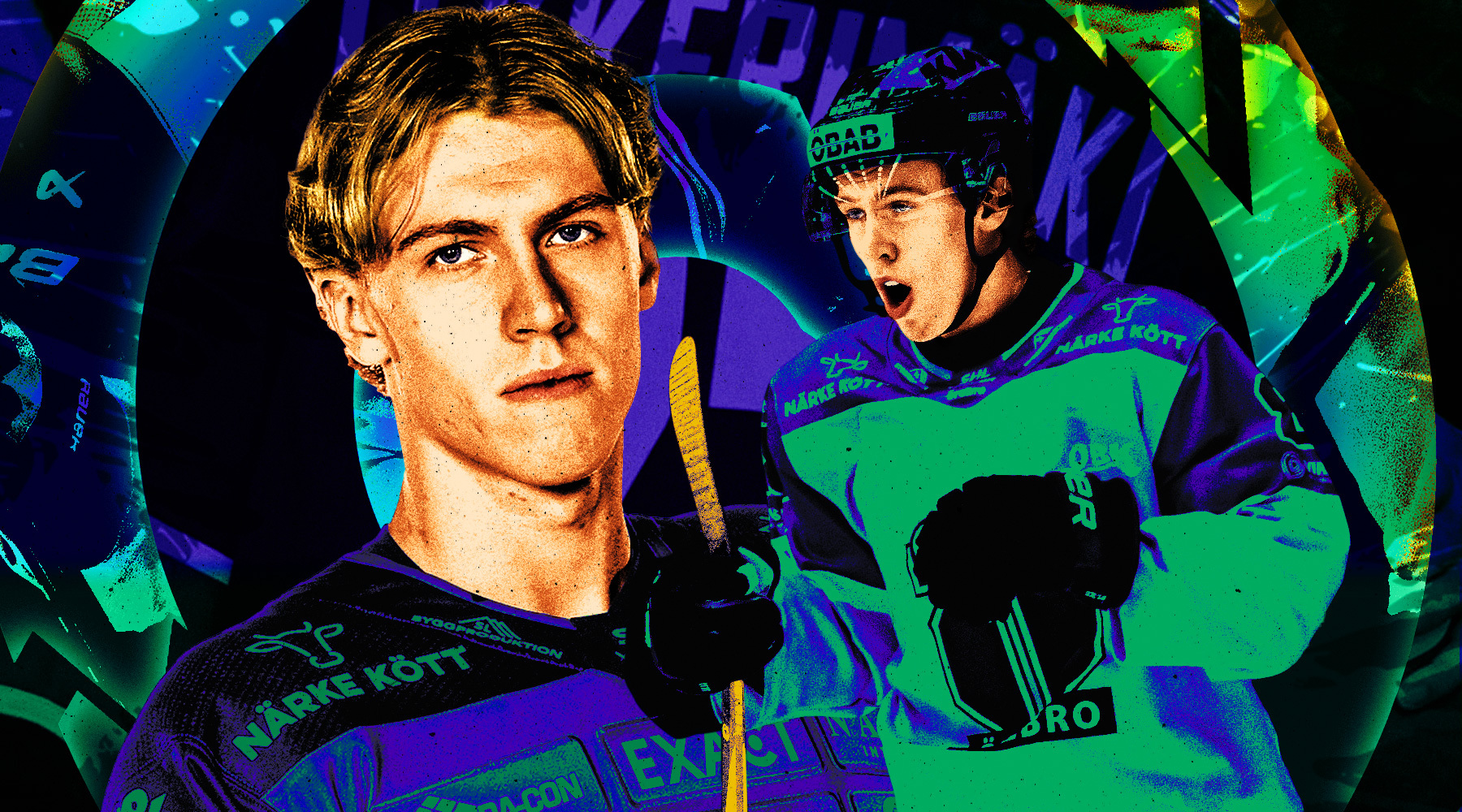

Now, the country will be more enthusiastic about this tournament than they've ever been, and the host city will have three players from their local team on board.

“We’ve got three players from it on the team right now, with Otto Stenberg, Isac Born, and David Edstrom. It all started with Henrik and Joel Lundqvist. Alexander Steen, my assistant coach, he played at Frölunda,” Hävelid said. “You look at Lucas Raymond. The tournament right now being in Sweden, that is the right city. I know they are very proud of it, too, as an organization. It’s just the right city for the tournament in Sweden.”

The IIHF awarded Sweden the tournament back in 2016, but not quite this one. It was awarded the 2022 World Juniors to start. Then something called Covid happened. Canada lost a tournament, then had to host one without any fans, and they felt that they deserved the opportunity to host one again to make up for lost revenue – fair enough.

The competition then began in earnest within Sweden to be the host city. Three cities put forward proposals: Stockholm, Malmö, and Gothenburg.

“I think the Swedish federation saw that Gothenburg is willing to do this together. They see that Gothenburg is one big part and they see that Frölunda is with us. The City of Gothenburg has sent out a signal that this is a really big tournament for us,” Ström said. "I think also the distance between Frölundabord and Scandinavium, because it’s only 15 minutes with the train – that’s good for the tournament.

“The feeling is that this time, Gothenburg is ready for the tournament. Everyone feels that we’ll do good work. I also think Frölunda’s program’s history is one thing, too. Right now, we have key players from the Swedish teams in Frölunda, and they see that we work hard with the juniors. The World Juniors is the best tournament to have in Gothenburg right now.”

The reception has been great from the locals. Exact ticket sales data is hard to come by, but the belief within the federation is that they've sold out every Swedish game and all of the medal round games, too. You're lucky to find something on the resale market for a medal-round game that's less than 150 CAD. All signs point to a hell of a tournament for everyone involved.

“You can see fans in World Juniors colours right now. We have flags at the bus stops in the city, of course. Hopefully, in the city we have a lot of things that display that the tournament is in here, but not much in the outside of the city. We’ve worked hard for a long time now. We worked hard with the clubs around us. And if we win, the parade goes through Gothenburg.”